Forbidden, Forgotten and Eradicated. But Alive

A new exhibition of Ukrainian avant-garde art is open in the Kumu Art Museum in Estonia.

They all arrive at their place of employment through the back door. They sign in, pass the bullet proof vests and walk through the vast galleries, where no pictures are hanging on the walls. The basements, collection spaces and archives of this museum are also empty. I would like to see these rooms, but even the emptiness is guarded in this place so carefully that no permit is given. It just isn’t possible. All of the most important treasures of the National Art Museum of Ukraine were taken west of Kyiv when the full-scale war broke out and were hidden. „In special places,“ the director Yulia Lytvynets states laconically, and for the first time during our conversation her wording is very precise.

The director of the Mystetskyi Arsenal complex, Olesia Ostrovska-Liuta, woke up early on that February morning. On her way to work, she wrote two letters in her car. One announced to her colleagues that the works had to be moved and all who wished could temporarily „transfer to other locations“ (she didn’t use words like „flee“ or „evacuate“ because she still could not believe what was happening). In the other letter, she asked her colleagues to prepare a letter to the world. Then she handed her daughter over to a colleague who promised to take her to a safe place: Bucha.

The art historian Oksana Semenik was already in Bucha. She had only recently moved with her husband into a new flat and had settled in. A couple of days after the arrival of Russians, they moved out and hid in the basement of the local kindergarten, where they stayed without water and food for many weeks. The neighbours who had remained above ground were shot when they went to get water. Their own flat was occupied by soldiers, who stole random things: a belt, a lens cap of a photo camera etc.

The summer cottage of the curator Olha Melnyk is not far from this kindergarten. During the first days of the war, rockets started falling on this quiet oasis amidst the pines. The Russians had a succinct name for the rockets: hail. They fell and fell, mowing down everything in their path. There is now a small piece of the trunk of a pine tree on the window sill of Melnyk’s office and she points out a tiny black fragment inside it: a reminder of a rocket. Beside this piece of wood on the sill is an icon. On her small desk are two small European Union flags and her walls are adorned with pictures of soldiers. From her window you can see a monastery with a police car in front of it with flashing lights: the monastery is being searched. Emblems of the whole of Ukraine’s recent past can fit into the few square metres of her office.

Some coloured drawings have also been tacked to the walls of Melnyk’s office. Rectangular people in theatrical poses. Rhomboid-like heads. Triangular legs. These are works of the Ukrainian avant-garde from the 1910s and the 1920s, a splendid period in the art history of the world which was imitated, copied and used as a role model from Paris to Berlin. Only, nobody knew that it was all made in Kyiv, Kharkiv, and Lviv. They thought that it was the world famous „Russian avant-garde,“ made by Russians in ancient Russian territories in accordance with Russian tastes.

„We had Russian museums and we had Ukrainian museums,“ says the department head of the National Art Museum of Ukraine, Olena Kashuba-Volvach. „Russian museums contained paintings and sculptures, and Ukrainian museums carpets and tapestries.“ In the university their generation was not taught about the existence of the „Ukrainian avant-garde.“ When they came to work in the museum, they started hearing rumours about it, but could not see those works. In the old building of the art museum, a special storage room existed somewhere in the basement with grey iron doors hiding the whole glorious era, with only the director and the chief registrar knowing the location of this collection. The works were hidden for decades.

Then the 1990s began. After long decades, the forbidden art was once again brought out, exhibitions were organised and people could, for the first time, see this large part of their art history. „I was very surprised,“ states Oksana Barshynova, who is one of the most renowned experts of this period. Even artists knew nothing about their modernist predecessors and the general audience was simply stunned. Only now could they see their true art history, and how patterns and motifs which originated in Ukrainian villages had influenced their own avant-garde authors, who, in turn, influenced other avant-garde artists. „Ukraine was an atypical colony because it donated the ideas that were disseminated in the Russian Empire,“ Melnyk adds. And not only in Russia. However, the Russians claimed it all as their own.

During the Soviet era, appropriation occurred through killing, prohibiting, destroying, and hiding Ukrainian artists and their art. Then in the 1990s, Moscow quickly understood that culture always equals politics. The taps were turned on and large exhibitions were organised in Europe, catalogues were published and grants were generously handed out to researchers from Russia and abroad. This led to the understanding that the avant-garde contained certain axes: Moscow-Berlin or Moscow-Paris, but Kiyv… well, you know, there they baked pies. The „Russian avant-garde“ brand was skilfully established and the world art market, which is one of the main creators of cultural memory, lapped it up greedily.

In Ukraine, nothing similar was undertaken. The annual funding for culture was so minuscule that even a couple of years ago, the then Director of Development at the National Art Museum of Ukraine had to negotiate with entrepreneurs for the paint to cover the walls. Nobody travelled. No books were published. The exhibitions were meagre. No researchers from Europe visited because they thought that Ukrainian art had nothing to offer. But Ukrainians themselves were equally ignorant of their own history. They hadn’t seen or heard anything because Russians had appropriated everything. „They have been plundering our culture for a thousand years“, the art historian Nadia Pavlichenko states. „But when it comes to the Ukrainian avant-garde, this pattern is especially clear.“

When I ask the Ukrainian Minister of Culture, Oleksandr Tkachenko, why Ukrainian culture has been loathed so passionately but has been appropriated with equal passion, he clears his throat and looks me straight in the eye. „They decided that Kyiv is the heart of Russia,“ he says. „But what can you do without your heart?“

No large exhibitions of Ukrainian art have taken place in Europe for decades. After the full-scale war broke out, there was a short surge of interest, but according to Olya Balashova, it is not sincere. „It is only emergency aid,“ she announces in another delightful side street of Kyiv, where we sit in the back office of a small alternative gallery.

„They don’t have any real interest or understanding that Ukrainian art is – and always has been – a part of European art.“

In the West, they fear that since the public knows nothing about it, no one will visit such a show. The ticket offices will be empty, no queues will form, and money won’t flow in. Ukraine is also too poor and has been mostly indifferent about supporting such projects. That is why Ukrainian art is currently where it has been located for most of the last one hundred years: underground and not above it. As always.

Forgetting and destroying

The grandmother of Nadia Pavlichenko was turning eighty. She had lived for a long time, had seen and experienced different things, but there was one topic she had never discussed with her grandchild. She invited Nadia over and, for the first (and for the last) time, said a few terse words about the Holodomor. She was seven years old when the Russians intentionally caused a multi-year famine that led to the death of at least four million people. She saw it with her own eyes. Dead mothers, children withered from hunger. But she nevertheless kept silent because she was afraid. While in post-World War II Europe, people took pains to remember, preserve and recollect everything, in Ukraine, everything was done to keep silent and to forget the past.

At the beginning of the 2000s, Oksana Semenik was still in school when suddenly the news came that the history curricula had been altered. Students were told to go and ask their grandparents what they remembered about the Holodomor because it was now allowed. Semenik went to her great-grandmother, and she started talking. About how she went to the fields to sow seeds as a child, and a Russian soldier with a machine gun stood guard to make sure that the underweight children did not put any seeds in their mouths: if you ate even one, you would be shot in the head. Only then did Semenik understand why her great-grandmother would hide some of the chocolate and pears that they brought her. She was nearly ninety, but the fear remained: maybe Stalin would return, maybe there would be hunger again, maybe… „You always have to have something stored away,“ she would say, cutting the dried crust of the bread into small pieces and hiding it away.

Nobody could imagine if we had started talking about the Holocaust only a couple of decades ago, but the Ukrainian Holodomor was hidden away in a special storage area. When the first large exhibition dedicated to the victims of the 1930s took place in the Kyiv History Museum in the 1990s, many visitors stood with tears in their eyes. „So many had a personal relationship with the Holodomor,“ says Olha Melnyk. A personal relationship that had never been spoken about.

Melnyk recalls that the people from the surrounding area always visited the museum. It was located in the governmental district and the important officials, authority figures and bosses wanted to see the history of their country. But this exhibition they did not visit. They refused to believe that something like this was possible. „This rift in our society still exists,“ Melnyk adds. „The war has reduced the differences in the ways we remember, but has not removed them completely.“

The Holodomor began in 1932, and that year also marks the beginning of attempts to erase the cultural memory of Ukrainians. The destruction of Ukraine at all levels began: this had been attempted previously and is once again being attempted as we speak.

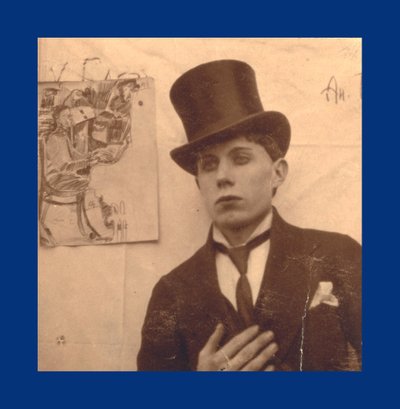

Associations of artists were prohibited. Then art that did not conform to directives started disappearing. One of these directives was the following: although the Holodomor was happening, art should depict fertile fields. The names of those who could not, were not capable of, or did not want to create this art were first crossed off the catalogues and later off other lists. In 1937, artists en masse were sent before tribunals and were shot. There were so many of them that that whole generation was referred to as the Executed Renaissance. In just one week in autumn, almost 300 of them were shot. The number of writers was reduced by ninety percent.

The relatives of the renowned artist Mykola Ivasiuk continued bringing food to the prison for him, but Ivasiuk had been shot a long time before because he didn’t paint correctly: he was indeed using the academic style but his ideas were nationalist. The family of the theatre innovator Les Kurbas also did not know anything about his fate. I stand with the director of the Museum of Theatre, Music and Cinema of Ukraine, Tetiana Rudenko, in front of a display. There are many such displays, but the most important assets of the museum have been taken to a place where Ukrainian art has been relocated time and again: into hiding under the ground. She shows me a list. It was discovered in an archive and it contains the names of all of the people who were to be shot that day. A tick with a ballpoint pen had been made in front of the name Kurbas: done, finished, next.

The executions continued after the war. Even as late as 1970, the artist Alla Horska was under surveillance by the KGB and then she was suddenly killed. A modernist composer was found hanging from a tree in a park. One artist was considered too European and therefore was banned from living in the centre of Kyiv: he would have a bad influence on the neighbours. In the end, he died kilometres from the heart of his home-town. And so it went, on and on.

Besides the artists themselves, their works were also destroyed or simply stolen, taken to Russia, and labelled as Russian.

„The first wave was after the Bolshevik Revolution,“ says Oksana Semenik, who has made herself up in the blue, black, and white of the Estonian flag in honour of our meeting. She is not the only Ukrainian art historian who knows by heart how many and which kinds of armaments Estonia has given them. „The second wave was during World War II. And the third wave lacks a clearly defined timeline because it was happening all the time.“ Throughout the Soviet era, for example, works were requested from Kyiv for exhibitions, were taken all over Russia and remained there. Just like that, without a word, nobody batted an eye.

Hatred of Ukrainian art rose to such a level that many Ukrainian artists hid their works… in Moscow. This seems paradoxical, but there the atmosphere was more lenient than in Kyiv, where people raged and destroyed art. The paintings by the renowned fresco painter Mykhailo Boichuk, which he had shown in 1910 in Paris at a special exhibition, disappeared almost completely. One of them was preserved by a student of his: he placed it between two doors at his home and plastered it up. Even that student himself was a rarity: Boichuk and nearly all of his students were killed and only a few, mostly female, students survived by escaping to Moscow.

Some works were saved by artists’ families, but not many. The largest contribution to the survival of the Ukrainian avant-garde was made by a Party member who had been appointed to evacuate works of art from museums during the war. Unlike the museum employees, he was also shown the innovative works contained in the special storage area and apparently he liked them. He selected some, sent them to the city of Ufa and, when they were later returned, it seemed somehow strange to place them back in storage. Such mistakes happened. The renowned Futurist painter Oleksandr Bohomazov made two versions of the same work: the differences were in insignificant details. One of the works was prohibited but the other one could be shown. Even idiots can sometimes make helpful mistakes.

However, this did not change the general picture. The hatred of the Ukrainian avant-garde remained, and whenever the opportunity arose, the whole of Ukrainian culture was vilified. One time all of the historical artefacts from the art museum were taken to another museum because the authorities needed more space for an exhibition about the history of the Red Army. In homes, family icons were destroyed and in the museum, permanent exhibitions were forbidden: two sides of the same coin. The objective was the same: to destroy, to hide, and to forbid. Nevertheless, just as a manuscript cannot be truly burned, works of art cannot really be destroyed.

Art

Icons. Folk art. Works by famous 19th century landscape painters whose technical skills were so masterful that you can only stare in silence. The history of Ukrainian art had been magnificent, and then, suddenly, the avant-garde was born at the beginning of the 20th century.

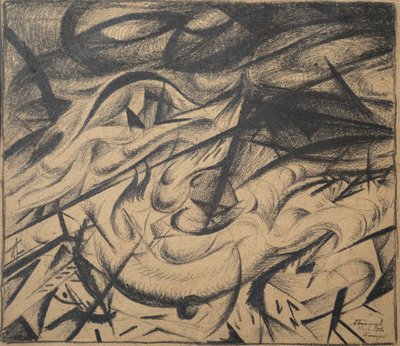

Artists went abroad, looked around, lived in Paris, and in 1910 opened an exhibition in Kyiv containing a couple of hundred modernist artworks which had only a year earlier shocked French audiences. A dialogue was started and newspapers wrote about modernity, with some praising and others condemning it, as always happens. And then the explosion. Suddenly Ukraine had dozens of artists who experimented with Cubism and Futurism, transformed them, investigated colours, and wrote theoretical dissertations.

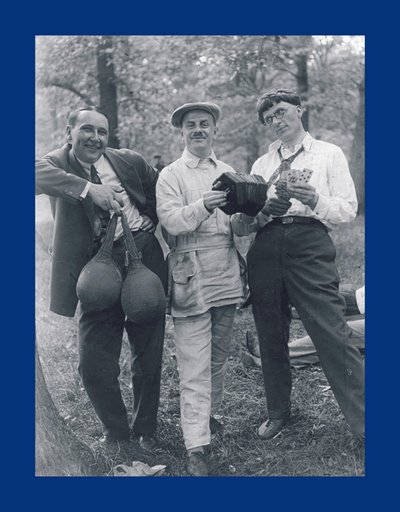

Western role models might have lit the fuse but an original Ukrainian avant-garde quickly developed, and it was characterised by vitality, emotionality, and totality. „Ukrainian Futurism encompassed all areas of art and life in general,“ says the curator Ihor Oksamentyi. We were walking through the enormous but currently empty spaces of the Arsenal. „Did you know that this was once a weapons factory?“ he inquired, adding a Ukrainian smirk: „Ironic, isn’t it?“

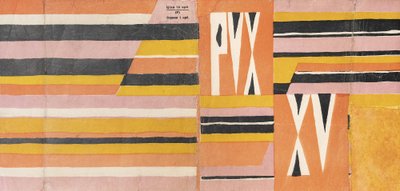

According to Olha Melnyk, Ukrainian Futurism was less radical than the Italian original. It used elements from various areas of art, extensively reflecting local traditions. „It is like a dappled carpet,“ Oksana Barshynova adds. For example, you look at art from Kyiv and see art from Munich or from Paris. You turn to Odesa and it is somehow softer and more synthetic. Consider the avant-garde of Lviv, and you will notice the influence of the great Austro-Hungarian Empire. In Kharkiv, there are influences of Russian art and traces of the folk tradition. However, when it comes to Kharkiv, you can only think about its art, since none of it has been brought out of the city. It is hidden in some mysterious basements, but the bombing is so intense that they are afraid: if they start evacuating artworks from the city, the trucks might get hit, and the works might be destroyed. Imagine such fears in 2023 in one of the centres of the European avant-garde!

Until 1917, Ukrainians worked with very different forms of innovation, delving into the problems of art itself, but also using it to energise national self-awareness. There are many who say that you can look at the Ukrainian avant-garde and see the glimmers of Ukrainian folk art instead. „I watched peasants working with great sympathy, assisted them with plastering the floors of their houses with clay and painted patterns on the stoves,“ the great Kazymyr Malevych once wrote. He admired the patterns, shapes, and colours he saw in the villages… and used them in his art in such a way that today we see the echoes of these villages in world famous museums without even being aware of it.

I gaze at these works and notice how much dynamism, conflict, drama, and brightness they contain. The works come to life, explode with passion, and there is always a strong theoretical foundation. „Compared to the Russian avant-garde, ours was more vital, it contained more life and was more emotional,“ Olena Kashuba-Volvach says.

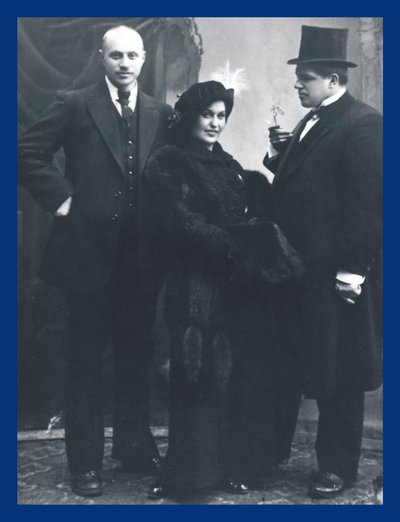

Women artists played an important, sometimes even a trailblazing, role. For example, Oleksandra Ekster was a superb artist who once, during an exhibition of folk art at an art museum, took traditional Ukrainian carpets and shawls and hung them on the walls diagonally in a manner that was similar to the broken lines of Futurism. „She changed the viewing perspective,“ states Yulia Lytvynets. The audience got used to and no longer avoided the strange avant-garde. Even Ukrainian icons resemble the avant-garde: they have very bright colours, are spatial, and do not always depict people, highlighting instead rhythms, lines, and patterns. The transition from folk art to avant-garde in Ukraine was astonishingly effortless because there was almost no need for a transition.

At the beginning of the 1920s, everything, of course, changed. Suddenly the avant-garde obtained a social function; artists were seen as purveyors of the new order and had the support of the state. Olha Melnyk uses her computer to show me short clips of people marching through towns and stopping in front of buildings based on the new rules. I look at the piece of pine shot down by the Russian rocket on her window sill and hear how the Soviet Union used to support the Ukrainian avant-garde a hundred years ago, seeing it as their ally. „Together they wanted to educate the public and create the new citizens,“ Melnyk states.

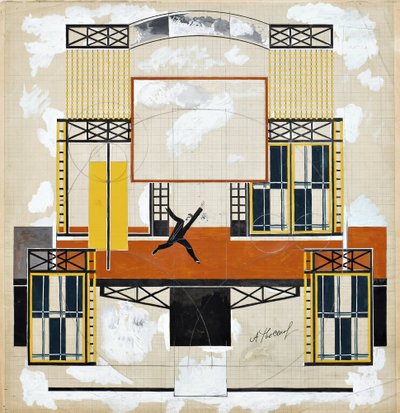

One artist even designed a special lectern that could be used for rousing speeches. New kinds of residential buildings were supposed to stand near factories, where flats would not have any kitchens because people would eat jointly in the cafeterias and children would be raised in separate complexes. People would focus on work and the rest would be taken care of by the benevolent state. Such dreams existed for both the country and art.

And then suddenly a great change occurred in 1932. The state decided that Ukrainian art would no longer be supported. And soon artists were killed, and their works were destroyed, stolen, or hidden. On the other hand, the works might be shown, the artists were named, and texts would be written about them, but everything was called… Russian art.

When I ask middle-aged Ukrainian art historians what they were taught about the Ukrainian avant-garde at university, they shake their heads with slightly ironic smirks. Nothing was taught. Famous professors had talked with Lytvynets about the Russian avant-garde, but nothing about the fact that many of those artists were actually Ukrainians. And this continued until the 1990s, when Ukraine became independent. Then some knowledge began leaking out, but nobody went to any great pains over it. Earlier, the people of Ukraine were forced to forget about their past and their artists, but now they were forgetting them voluntarily.

When the Estonian ambassador to Ukraine, Kaimo Kuusk, was in the hospital for many weeks as a child, he had a lot of free time and learned how to read. He read a sumptuous book about Russian heroes and was especially taken by Illia Muromets. Forty years later, when he was walking in Kyiv as the head of the Estonian Foreign Intelligence Service, the Ukrainian secret police officers suddenly asked if he would like to see the grave of Muromets: it was there, in the subterranean caves under the centre of Kyiv. Only then did Kuusk understand that Muromets was a Ukrainian and not a Russian hero. Nobody had told him this earlier, not even his Ukrainian grandfather.

Colonisation

Olya Balashova’s grandmother spoke Russian with her daughter. When the daughter was older, she felt that she wanted to be a normal Soviet citizen like everybody else. In Ukraine, this meant only one thing: you had to give up the Ukrainian language and use Russian. With her daughter Olya, she only spoke Russian.

But when the full-scale war broke out a year ago, Olya’s mother refused to speak Russian. She just stopped and switched to Ukrainian, which her mother had used to speak with her when she was a child. „It is strange,“ Balashova says smiling. „She no longer sounds like my mother.“ Balashova also refuses to speak Russian. „It is the language of the enemy,“ she says about her mother tongue.

When schools were opened in Ukraine during the Soviet era, a town might have two Ukrainian-language schools but ten or fifteen Russian ones. And the Ukrainian schools definitely had to have separate Russian classes. When a new play was staged, the first version was in Russian, and only when the whole town had already seen it would it be staged in Ukrainian, but never with a higher number of performances than in the Russian theatre. „Only books by Ukrainian writers or about the history of kolkhozes were published in Ukrainian,“ states Oksana Semenik. When she wanted to read Balzac or Hemingway, the only option was to find a cheap Russian edition. It is no wonder that up until recently, Ukraine had over 400 streets named after Pushkin, and hundreds of streets, even in the smallest of villages, bore the names of Tolstoi or Lermontov. However, only a few carried the names of Lesia Ukrainka or Nataliia Kobrynska.

Almost no journals were published in Ukrainian, doctoral dissertations had to be defended in Russian and in Moscow, TV series for teenagers were only in Russian, and Ukrainian baroque music was presented as Russian baroque. There was a famous saying: in Moscow they cut the nail, but in Kyiv the whole finger. However, the nail which they hacked away in Moscow was usually a Ukrainian nail.

Even in the 2000s, respectable Russian art historians would talk with their Ukrainian colleagues about „Ukrainianism“ as if it was some sort of a joke. „If they had to speak about our authors,“ Olena Kashuba-Volvach declares, „they could not say ‘Ukrainian authors’, but had to use the term ‘artists from Kyiv’.“ When I ask her if she has received any private messages from former Russian colleagues saying that they understand what was happening, offering their support or at least sympathising with Ukranians, she quickly shakes her head with a wry smile. Nothing. Zero. When Crimea was occupied, she received a letter from St Petersburg asking for her expertise on a painting, and she answered with a lengthy analysis of the work, ending her reply with the words: „This is war. Slava Ukraini!“ She has received no new letters from Russia since then.

„Ukrainian intellectuals are politically very active, like their European counterparts,“ says Olesia Ostrovska-Liuta. „But Russian intellectuals aren’t active and that is shocking. We were expecting more from them, including from the ones now residing in Europe. But we no longer hope for it and this feels liberating.“ People in Ukraine understand that Russian intellectuals do not take positions, and just do what they are told. „Since 2014, I no longer communicate with Russians,“ Yulia Lytvynets adds. „For me, they are dead.“ This is because Russian art historians who call themselves humanists have done everything in their power so that Ukrainian art will be called Russian art, thereby destroying the Ukrainian identity.

Decolonisation

„The Ukrainian people are like the survivors of a shipwreck who find themselves washed up on a beach,“ Olesia Ostrovska-Liuta says in her office, which is squeezed into a room of a Khrushchev-era block of flats. „They slowly start feeling their own bodies, trying to decide if they are still alive. ‘What is this part of my body? What about this one?’“ And slowly, the Ukrainians are starting to discover who they actually are.

„The question of nationality is, of course, problematic,“ Iryna Bilan says. „It is very hard to say who is Ukrainian, Polish, Russian, or Belarusian and to what extent.“ During the first night of the war, she slept in her flat’s corridor, away from the windows. Since then, she has often volunteered to pack boots, knee pads, uniforms, and medications for the people on the front: now a part of the everyday life of a Ukrainian art historian. She is a cultural producer from a younger generation, and I get the feeling that she and all other Ukrainian art historians would like to consider very different questions than what kind of blood flows in somebody’s veins.

Ihor Oksamentyi points out that when the exhibition of Futurism was opened in Kyiv, they did not want to work with the tragic side of their past. „We wanted to talk about a phenomenon,“ he adds when we are parting during a cool spring evening in Kyiv between two air alerts. Many believe that Ukrainians have never really loved their state, but they do love their freedom. Thinking of themselves as martyrs, even though millions have been killed, is not part of their nature. „We wanted to free Ukrainians of the idea of seeing themselves as victims,“ Olha Melnyk explains. That is why the exhibition had to have the title Futuromarennia. „We did not want to speak about the past, but the future,“ Melnyk says. „Not about the suffering, but about progress.“

However, now everything is different. Not only the names, but the whole culture has to be restored, so that people in Ukraine, as well as the rest of the world, understand what Ukraine actually is. Currently, this understanding doesn’t exist.

When Oksana Semenik escaped the basement of the kindergarten in Bucha carrying her cat and fleeing towards the capital through the spring mud, she thought: how could she, an art historian, help the soldiers of her country? Now she sends letters to American or European museums almost daily, pointing out that they are identifying the Ukrainian Malevych as a Russian or when a painting shows a person in Ukrainian folk costume, the title maybe shouldn’t be Young Russian Girl. Sometimes Semenik receives a pleasant answer and the contacted museum gets to work making changes. But then the dawdling usually starts. The world-renowned Brooklyn and Smithsonian Museums haven’t even bothered to reply to Semenik. Or if the replies do come, they grumble: „Why do we have to write Odesa, Kharkiv, or Kyiv and not ‘former Russian Empire’“? Semenik is passionate when she asks me in a small pastry shop in Kyiv: „Why don’t they say ‘former English Empire’ about India? Why are they reluctant when it comes to Ukraine?“

When Semenik was working in the USA, many of her Russian colleagues would say that replacing a place name in a database would be too complicated. „Couldn’t we use ‘Soviet artist’ instead of ‘Ukrainian artist’?“, a highly educated colleague and part-time humanist asked her. „If we did that, we could also use the term ‘Third Reich artist’ when talking about German authors,“ Semenik adds with disdain.

She is not the first one to attempt this transformation. As early as the 1990s, many Ukrainian museums started writing their Western colleagues and asking why Illia Repin, who was born and raised near Kharkiv, couldn’t be called Ukrainian. Or what about one of the most important woman artists of the beginning of the 20th century, Oleksandra Ekster? Or the renowned Burliuk brothers, Abraham Manevych and Borys Kosarev? They received no replies.

On the internet, Semenik is quite reviled. She has been attacked on Twitter and Facebook, but she merely shrugs. Because complete Western indifference is what actually riles her up.

Indifference

„You know the answer,“ Olesia Ostrovska-Liuta smiles and doesn’t add anything for a couple of seconds. I had asked her if there had been any interest from Europe in Ukrainian art history, but the answer is indeed clear without asking. „Big powers are interested in other big powers,“ she says calmly in her modest office and passes me some first-rate scientific publications about Ukrainian art.

Before last February, they had discussed with their colleagues on numerous occasions why even their closest neighbours are not interested. Once, in Berlin, she entered a bookshop and saw that books about Ukraine had been placed in the section „Smaller languages“. The country has over forty million inhabitants, but it is still labelled as „small“, which is synonymous with „unimportant.“ Yes, since the invasion began, there seems to be a bit more interest in Ukrainian art, but Ostrovska-Liuta does not believe that the reason for this is the art itself. „Only when we started resisting did they get interested,“ she adds. „We had to spill our blood and make some gains to be noticed.“ A mixture of violence and hope is the narrative which sells in the art world, but it doesn’t sell enough.

Once the Ukrainian pavilion at the Venice Biennale was located next to the one showing Modigliani. In 1925, the modern stage design by Vadym Meller won a gold medal in Paris and, when it was later taken to New York, people were so shocked that they had to touch it to see if it was real. The Ukrainian avant-garde was of such a high level that Davyd Burliuk has been called the father of both Russian and Japanese Futurism. Without Kazymyr Malevych, most Western art history would simply not exist. Despite this, only a few offers for exhibitions have been sent from Europe to the most important art institutions in Ukraine.

Contemporary Ukrainian art is also ignored. In the last year, three of the most important art exhibitions in Europe included no Ukrainian artworks. None. „Contemporary art has lost its sense of smell,“ Olya Balashova states. „Art can and should sense and diagnose difficult and dangerous situations that no other instrument created by humans can. Overlooking Ukraine is a failure of contemporary art.“

We are sitting in the back office of the small alternative gallery „Naked Room,“ which is located on a side street of darkening Kyiv. Olya has a slight cold, we drink tea, and behind her is a small rainbow flag: a sign of solidarity. She tells me excitedly about contemporary Ukrainian artists. One of them made her paints with soil from Bucha, which due to its high clay content turns them somewhat red. Two authors made a video showing them collecting junk metal from an exploded Russian tank, and murmuring prayers to protect themselves from getting bombed. An artist group gathered together the materials used for an exhibition in a gallery and promised to send them to assist with the renovation of bombed houses. A museum held an exhibition about the evacuation of their collections. Artists from all over the city came to help with this effort and the exhibition also contained a display with a shoe from one of the helpers: a sign of war-time solidarity. But all of these exhibitions took place in Ukraine.

„Ukraine and its art have been a blind spot for Europe for the last hundred years,“ Balashova says. She does not believe in the sincerity of the curiosity of today’s Europe. „Ukraine has no interesting artists,“ a curator of a major and important exhibition in Europe said some decades ago… without ever having visited Ukraine. When Crimea was occupied, there was a slight surge of interest, but it faded away quickly. „This was a failure of the West,“ points out the Flemish director Björn Geldhof of the Pinchuk Art Centre, which is one of the most important contemporary art institutions in the country. „The Ukrainian narrative was not constructed, because it was not in the interest of the West.“

In February, the director of the renowned Musée d’Orsay announced that the Ukrainian artist Oleksandr Murashko (who had exhibitions in Rome, Berlin, Munich, Venice, and Amsterdam at the beginning of the last century…) was not known by anybody in France and there was no reason to even talk about him… and instead organised a discussion of Russian art during a dusky evening in Paris. Some Ukrainian museums were being robbed of everything at the same time. Some other works were destroyed, some memories erased, but in the heart of Europe it was all un petit champagne and famous names. One of them said that Ukraine should not think about retaking Crimea, even after she herself used the word „occupation.“

When I asked where exhibitions of Ukrainian art have taken place abroad over the last thirty years, the answers were recited by heart: Winnipeg. Toulouse. Zagreb. They are certainly wonderful places, but art history is not written there. Indeed, many of these exhibitions were organised by members of the Ukrainian diaspora. Nobody else saw any value in the history of the art of this country of forty million people. „Western museums joyfully accepted the relabelling of Ukrainian art as Russian art,“ Geldhof adds when I call him from the airport in Warsaw. „They were either Russophiles, had good relations with Russia or it was because of financial reasons. But they lacked a critical viewpoint.“ Or they lacked any viewpoint whatsoever.

Future

On my way to the art museum, I pass Maidan Square. Some days before, thousands had gathered to pay their respects to a hero who had died in battle. His nickname was „Da Vinci“ because he wanted to become an artist one day and filled all of his spare moments with drawing. But then came Maidan, then Donbas and Crimea. He went to war, performed heroic acts, and became the youngest military leader ever. „I thought he was immortal,“ a friend of his says grimly in a café.

The president, the prime minister, the head of intelligence, and the commander-in-chief of the army knelt next to Da Vinci’s casket with the latter also kneeling in front of the hero’s mother and placing his head in her lap. „It is extraordinary how Ukraine can touch the deepest memories of the European soul,“ an analyst who had witnessed this wrote. „It is like Ancient Greece, the Roman Republic, or Medieval kings. All of the art and literature and thought and actions of Europe are captured by this image. Today, Europe is foremost alive in Ukraine.“

Art life in Kyiv has never ceased. Two weeks after the Russians left Bucha, the first exhibition in „Naked Room“ opened. In Kyiv, only two public spaces were open: a bar and this gallery. „During the war, people really do need art,“ Balashova says. „It gives meaning to life and you can feel something besides anger and rage.“ When the power station was attacked, the exhibition in the Arsenal was installed using pocket torches, and the exhibitions were kept open for longer during the weekend, because large industrial complexes were closed and there was enough electricity to go around. „We had a very warm reception,“ Olesia Ostrovska-Liuta states. „People still want to live their lives.“ Many students have said to Oksana Barshynova that only now, after Bucha and Irpin, do they really understand what Picasso’s Guernica really means: art has acquired a different meaning.

These days, Ukrainian art life is active 24 hours a day and people are somewhat irritated if the replies from Europe don’t arrive for many days. Museums are active and the Ukrainian Minister of Culture adds with clear pride that three quarters of the people active in culture remained in the country, there were fifty theatre premiers during the last year and audience numbers have not waned. „Their reactions are more emotional than before the war,“ Oleksandr Tkachenko adds in perfect English in his Soviet-era office where somebody else from abroad had just left before I came in. „Theatre is more than psychotherapy: people are grateful that those working in culture remained here.“

The Arsenal complex decided that instead of reducing the number of staff they would hire more. „If we don’t culturally associate with Europe, we don’t have a chance,“ Olesia Ostrovska-Liuta believes. In a couple of months, they learned the vocabulary of decolonisation and are trying to persuade Europe that Ukraine didn’t just copy European art and that the relationship was between two equals instead. It is not very easy because important curators are still not present in Kyiv. Olya Balashova does not believe that this is only because of fear, since Kyiv is relatively safe. „Kyiv is the liveliest place in Europe,“ Balashova insists and she has travelled a lot over the last year. „Here you can truly feel alive.“ The classmates of one of my acquaintances work as bankers in Canada, drive around in Mercedeses and live in their safe homes, but they envy the friends that remained in Kyiv: they feel that this is where the actual change is happening.

The Pinchuk Art Centre’s director Björn Geldhof is optimistic. He is one of the few Europeans who has been consistently interested in Ukraine and has worked there for more than a decade. „The audience here is different than in the West,“ he says. „Very young, very numerous, and very curious.“ 80% of the visitors to their centre are younger than thirty and this is unlike anywhere else. But Ukraine lacks an academic approach to their recent art history and this is something that the Ukrainians themselves are trying to change. Numerous institutions are starting new archives, raising funds to purchase contemporary art, and founding new collections amidst air raid alerts, drone strikes, and the deaths of their loved ones. „We have a very spirited debate about what makes Ukrainian art Ukrainian,“ Geldhof states. He does not believe that geography or the origin of the artist should necessarily be the basis and instead points to a certain „attitude“.

When it comes to the future, he is very bold. Unlike art historians, he has noticed a surge of interest. Ukraine is suddenly popular, and the spilt blood and the corpses lying in Bucha or Bakhmut have piqued the interest of the European art world. „Our aim is for this interest to not merely be a short burst,“ Geldhof adds. „It has to become consistent, and various institutions should acquire Ukrainian art for their collections and organise exhibitions. This is the only way the mentality of Europe can be changed.“

Therefore, the exhibition taking place in Tallinn is important for Ukrainians in many ways. But the director of the National Art Museum of Ukraine, Yulia Lytvynets, will not be going to the opening. „What if something were to happen in Kyiv at the same time?“ she asks. The museum is empty, the works are hidden in bunkers, but she still feels responsible for the museum and feels she must remain in the city.

Before I leave the Arsenal, Olha Melnyk takes me to see the installation which has been made specifically for the exhibition of Ukrainian Futurism in Tallinn. It shows small pictures exploding, accompanied by the sound of breaking glass. „We didn’t want to include the sound of explosions,“ Melnyk points out. „Glass can break easily. But it is also easy to repair.“

Nobody I meet in Kyiv is pessimistic. Far from it. „When Putin dies, we will hold a rave on his grave,“ Oksana Semenik announces. „And our generation will tell our grandchildren to always have charged batteries.“ They live for the future. A future where they have reclaimed Ukraine.

I thank Oleksandra Havryliuk, Matti Maasikas and Karin Maandi for their assistance in arranging the interviews.

***

Translated by Peeter Talvistu